Life wasn't easy for Shelly Bauman, and she knew it. She was kicked out of home at an early age, left with an injury in her early 20s that would debilitate her for the rest of her life, had two marriages, two divorces, and struggled with drugs all her life.

'The impact that bar had on the Gay rights movement is pretty profound,' said Monte Levine, Shelly's caretaker during her final years. 'I mean we're looking at less than four years after Stonewall.'

Shelly was born in Illinois on July 23, 1947. She grew up in Chicago, where she studied dance. In the summer of her 16th birthday, her father committed suicide and her mother told her that he was really not her father and kicked her out of the house forever. After this, life was rough for Shelly, a trend that would continue throughout her 63-year life.

'She never really recovered from being kicked out,' said Levine. 'She had trouble trusting people, and without trust, you cannot have love.'

After leaving home, she became an exotic dancer to support herself. She moved around the country - Chicago, Miami, Hawaii, and to Fort Myers, FL, where her family had spent their summers in her youth.

Shelly ended up in Seattle in the winter of 1968 and she was taken in by a black family living in Rainier Valley. She continued dancing until the day of her fateful accident, which would inadvertently lead not only to the creation of her bar, but to the name itself.

Shelly and a group of friends went to Pioneer Square on July 14, 1970 for the Bastille Day Parade.

'There was a cannon in the parade loaded with gunpowder, held in place by a wad of wet paper-mâché,' wrote Shelly. 'Someone lit the fuse and the cannon fired into the crowd, hitting [me] in the pelvis. It was the son of the owner of the cannon showing off to a friend.'

The blast took part of Shelly's pelvis, a kidney, some of her intestines and her left leg - after that, there was no more dancing for Shelly Bauman.

She described the blast as lifting her up in the air and landing her flat on her back. She slipped out of consciousness quickly and went comatose, not waking up for almost a year. It took two years for Shelly to get out of the hospital, and even longer for her to win her lawsuit.

It was during this time that she met Peter Nesser, a Gay man whom she moved in with the next day. He owned a large house in Rainier Valley and rented out rooms to other Gay men. The two chatted about opening a bar with part of her settlement money - very quickly, it became a reality.

'Peter wanted to name it the -Great White Swallow,' wrote Shelly. '[I] wanted to name it -Shelly's Leg.'

The first disco in Seattle opened November 13, 1973, just a few years after Stonewall - and Seattle's first disco was a Gay Bar.

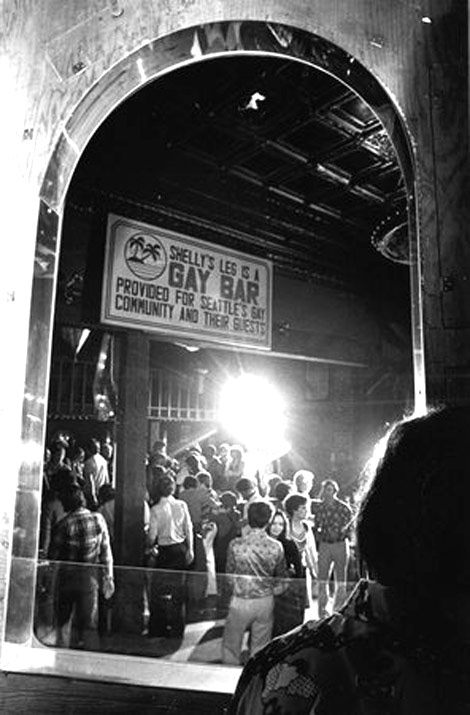

Shelly's Leg housed 1940s lounge decor along with fake palm trees and neon lights. The bar was very successful, with weekend lines that stretched around the block. The 'in crowd' - the Gays - often went though a special entrance at the back where their names were listed in a Rolodex.

One of the most recognizable aspects of the bar was a 4x8 sign posted in the foyer that proclaimed: 'Shelly's Leg is a GAY BAR provided for Seattle's Gay community and their guests.'

'As word spread through town that there was this great place to party, more straight people began to frequent the bar. Tensions rose and Shelly's Leg ended in 1979. [I] wanted a place where everyone would feel welcome, no matter what their sexual orientation, identity, race, religion or other factors,' wrote Shelly.

In the wake of the bar closing, Shelly's doctor informed her that she was dying.

'It was a good run,' said Shelly. She packed up her belongings and moved to Hawaii.

In Hawaii, she met a native healer and her physical condition improved, but she then lost most of her belongings in a fire. Left with nothing, she fell in love with a man who happened to be from Fort Myers, FL. The couple moved to Fort Myers, they married, they divorced, and Shelly remained in Florida until 2002, living in a trailer near the water.

In 2002, Fort Myers was hit hard by a hurricane, once again leaving Shelly with nothing - the Red Cross gave her $750. She decided to call Levine, back in Seattle, whom she had met before her accident in 1969 and ask for help to relocate back to the Seattle area. She used the money to book a flight, and she was off.

'When she moved back to Seattle, she knew she couldn't live in Seattle proper, because of her love of drugs,' Levine told SGN.

She moved in with Levine and his partner Marc in Bremerton until there was a vacancy in the duplex the pair managed across from their house, and the two took care of Shelly until her death.

Levine and his partner coordinate one of the largest non-urban syringe exchange programs in the country out of their garage, and while she was living with them, she became very interested in the rights and plight of intravenous drug users.

Just after her 60th birthday in 2008, Shelly was stricken by yet another fire when she was smoking and forgot to take off her oxygen cannula. A neighbor, Rodney Jewell, noticed the smoke and was able to run in and rescue her just in the nick of time. Once again, all her possessions were gone.

Shelly was left with burns all over her body and the smoke from the fire - coupled with her history as a lifelong smoker of cigarettes, marijuana, and any other drug that could be smoked - deteriorated her lungs beyond repair.

'Shelly never went a day without experiencing physical pain. The psychological scars from her youth never had an opportunity for healing. All a dancer has is their body, and Shelly lost that a couple of weeks before she turned 23, and with that lost control of her life,' said Levine.

Shelly's final years were rough on Levine.

'Hell, anyone that knew the woman knew she was a pathological liar. & It's very hard to love and be a friend to someone who can't tell the truth. & Shelly told me I taught her three things: -please,' -thank you,' and -you're welcome,' Levine told SGN.

Shelly will always be remembered as a party girl with beautiful long red hair. A celebration of her life is in the works, which will fundraise for organizations that help people in recovery for intravenous drug usage.

The iconic sign from Shelly's Leg is now in the permanent collection at Seattle's Museum of History and Industry [James Whitely - SGN].

Life wasn't easy for Shelly Bauman, and she knew it. She was kicked out of home at an early age, left with an injury in her early 20s that would debilitate her for the rest of her life, had two marriages, two divorces, and struggled with drugs all her life.

'The impact that bar had on the Gay rights movement is pretty profound,' said Monte Levine, Shelly's caretaker during her final years. 'I mean we're looking at less than four years after Stonewall.'

Shelly was born in Illinois on July 23, 1947. She grew up in Chicago, where she studied dance. In the summer of her 16th birthday, her father committed suicide and her mother told her that he was really not her father and kicked her out of the house forever. After this, life was rough for Shelly, a trend that would continue throughout her 63-year life.

'She never really recovered from being kicked out,' said Levine. 'She had trouble trusting people, and without trust, you cannot have love.'

After leaving home, she became an exotic dancer to support herself. She moved around the country - Chicago, Miami, Hawaii, and to Fort Myers, FL, where her family had spent their summers in her youth.

Shelly ended up in Seattle in the winter of 1968 and she was taken in by a black family living in Rainier Valley. She continued dancing until the day of her fateful accident, which would inadvertently lead not only to the creation of her bar, but to the name itself.

Shelly and a group of friends went to Pioneer Square on July 14, 1970 for the Bastille Day Parade.

'There was a cannon in the parade loaded with gunpowder, held in place by a wad of wet paper-mâché,' wrote Shelly. 'Someone lit the fuse and the cannon fired into the crowd, hitting [me] in the pelvis. It was the son of the owner of the cannon showing off to a friend.'

The blast took part of Shelly's pelvis, a kidney, some of her intestines and her left leg - after that, there was no more dancing for Shelly Bauman.

She described the blast as lifting her up in the air and landing her flat on her back. She slipped out of consciousness quickly and went comatose, not waking up for almost a year. It took two years for Shelly to get out of the hospital, and even longer for her to win her lawsuit.

It was during this time that she met Peter Nesser, a Gay man whom she moved in with the next day. He owned a large house in Rainier Valley and rented out rooms to other Gay men. The two chatted about opening a bar with part of her settlement money - very quickly, it became a reality.

'Peter wanted to name it the -Great White Swallow,' wrote Shelly. '[I] wanted to name it -Shelly's Leg.'

The first disco in Seattle opened November 13, 1973, just a few years after Stonewall - and Seattle's first disco was a Gay Bar.

Shelly's Leg housed 1940s lounge decor along with fake palm trees and neon lights. The bar was very successful, with weekend lines that stretched around the block. The 'in crowd' - the Gays - often went though a special entrance at the back where their names were listed in a Rolodex.

One of the most recognizable aspects of the bar was a 4x8 sign posted in the foyer that proclaimed: 'Shelly's Leg is a GAY BAR provided for Seattle's Gay community and their guests.'

'As word spread through town that there was this great place to party, more straight people began to frequent the bar. Tensions rose and Shelly's Leg ended in 1979. [I] wanted a place where everyone would feel welcome, no matter what their sexual orientation, identity, race, religion or other factors,' wrote Shelly.

In the wake of the bar closing, Shelly's doctor informed her that she was dying.

'It was a good run,' said Shelly. She packed up her belongings and moved to Hawaii.

In Hawaii, she met a native healer and her physical condition improved, but she then lost most of her belongings in a fire. Left with nothing, she fell in love with a man who happened to be from Fort Myers, FL. The couple moved to Fort Myers, they married, they divorced, and Shelly remained in Florida until 2002, living in a trailer near the water.

In 2002, Fort Myers was hit hard by a hurricane, once again leaving Shelly with nothing - the Red Cross gave her $750. She decided to call Levine, back in Seattle, whom she had met before her accident in 1969 and ask for help to relocate back to the Seattle area. She used the money to book a flight, and she was off.

'When she moved back to Seattle, she knew she couldn't live in Seattle proper, because of her love of drugs,' Levine told SGN.

She moved in with Levine and his partner Marc in Bremerton until there was a vacancy in the duplex the pair managed across from their house, and the two took care of Shelly until her death.

Levine and his partner coordinate one of the largest non-urban syringe exchange programs in the country out of their garage, and while she was living with them, she became very interested in the rights and plight of intravenous drug users.

Just after her 60th birthday in 2008, Shelly was stricken by yet another fire when she was smoking and forgot to take off her oxygen cannula. A neighbor, Rodney Jewell, noticed the smoke and was able to run in and rescue her just in the nick of time. Once again, all her possessions were gone.

Shelly was left with burns all over her body and the smoke from the fire - coupled with her history as a lifelong smoker of cigarettes, marijuana, and any other drug that could be smoked - deteriorated her lungs beyond repair.

'Shelly never went a day without experiencing physical pain. The psychological scars from her youth never had an opportunity for healing. All a dancer has is their body, and Shelly lost that a couple of weeks before she turned 23, and with that lost control of her life,' said Levine.

Shelly's final years were rough on Levine.

'Hell, anyone that knew the woman knew she was a pathological liar. & It's very hard to love and be a friend to someone who can't tell the truth. & Shelly told me I taught her three things: -please,' -thank you,' and -you're welcome,' Levine told SGN.

Shelly will always be remembered as a party girl with beautiful long red hair. A celebration of her life is in the works, which will fundraise for organizations that help people in recovery for intravenous drug usage.

The iconic sign from Shelly's Leg is now in the permanent collection at Seattle's Museum of History and Industry [James Whitely - SGN].

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement